When I took my first introductory psychology course at university, I was fascinated by the idea of quantifying human nature. Personality tests seemed like a way to assign numbers to the mind. When we were asked to take a Big Five personality test ourselves, I was shocked by the results. I scored high in neuroticism, which naturally made me anxious—yet, perhaps also because I also scored high in openness, I was able to reflect on and even embrace that anxiety. That duality made me chuckle to myself a bit, but also sparked a deeper interest in the concept of psychological metrics that would inform my later career in marketing.

Years later, when I left the United States—first for work, and then for love—I often wondered whether my personality traits would help or hinder me in adapting to a new setting. The question didn’t feel formal; it felt personal. I carried those test results with me like a folded map: not a perfect guide, but enough to keep me oriented as I stumbled through novel streets.

I’m not particularly musical, and I assumed language learning was reserved for those with a “good ear.” Still, I studied diligently, focusing on pronunciation and grammar and stayed open to new linguistic experiences. The first time I made a joke in a foreign tongue and someone actually laughed, it felt like crossing an invisible border. I wasn’t just getting by, I was starting to participate with the world around me. But even when my language lagged, my willingness to take on new tasks and the extroversion I had absorbed from American culture helped me move forward when it came to work. Looking back, I realized those early personality results had foreshadowed parts of this journey. Extraversion gave me a way into local networks; openness made uncertainty feel like an experiment rather than a threat; conscientiousness kept me steady when the novelty wore off.

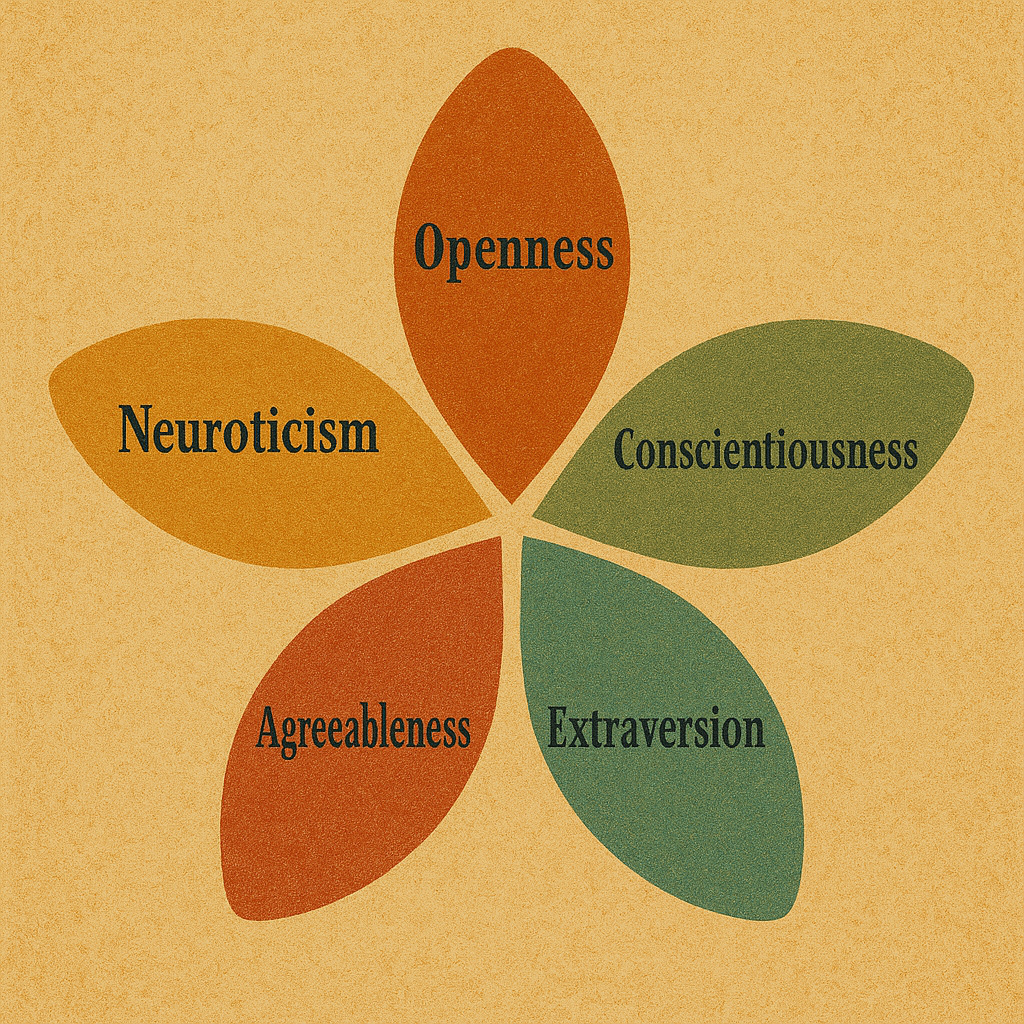

Only later did I learn how closely my story of integration tracks the research. A recent meta-analysis spanning 62 studies confirmed that each of the Big Five traits is positively associated with expatriate adjustment—with extraversion, emotional stability, and openness emerging as especially influential (1). In short, the “map” I carried from that classroom wasn’t entirely wrong. Traits do matter, not just in the abstract but in the daily work of settling into a new culture.

But the same research makes another, subtler point: personality is only the foundation. Characteristics that are more specifically intercultural—cultural empathy, cultural flexibility, and cultural intelligence—as well as emotional intelligence, tend to be even stronger predictors of whether we actually adjust well. It isn’t enough to be outgoing or open; you also need the capacity to read unfamiliar social cues, adapt your behavior, and regulate your emotions in a setting that may code meaning differently than your home culture. In other words, thriving abroad isn’t just about who you are—it’s about how well you learn the “grammar” of somewhere else (2).

This resonates with how my own adjustment turned a corner. What helped wasn’t a sudden boost in vocabulary or a personality makeover; it was learning to calibrate. When to speak and when to listen. When a modest nod does the work of an enthusiastic “Great job!” and when it doesn’t. How direct to be in making a request. And—perhaps most importantly—how to notice the small, local signals that tell you whether you’re warming up the room or cooling it down. Cultural empathy and flexibility gave me leverage where extroversion alone would have fallen flat.

Emotional intelligence (EI) sits right in the middle of this process. The ability to read my own anxiety without letting it run the show, to notice the strain in a colleague’s face without assuming insult—all of that proved just as practical as memorizing verb conjugations. The meta-analysis suggests EI facilitates both work and non-work adjustment, and that its effects often outpace those of broad personality measures once you’re actually navigating daily life.

Yet EI isn’t a one-size-fits-all skill. Culture shapes what “emotionally intelligent” looks like in practice. In some societies, emotional display is dialed down; in others, it’s a key part of signaling engagement and trust. A nine-country study finds that cultural values—especially collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation—help shape the different facets of EI. That means the behaviors we read as sensitive or skillful in one setting can misfire in another. A warm, openly enthusiastic American style can feel genuine in one room and oddly performative in another; a restrained, harmony-seeking style can communicate maturity in one context and indifference in another. The skill, then, is not just “have EI,” but “tune EI to the local channel.”

The research goes further, reminding us that situations tug back on dispositions. Factors like cultural distance (how different the host culture is from home), the “tightness” of local norms (how strictly they’re enforced), and gender inequality can amplify or dampen the impact of personality and intercultural skills. A highly extraverted newcomer may flourish in a loose, low-distance context where initiative is welcomed—and struggle in a tighter setting that prizes discretion and role clarity. Likewise, motivational cultural intelligence—the drive to engage with difference—seems to matter most when distance is large and the path through uncertainty is longer. This person-situation interplay is why adjustment feels easy on one street and baffling on the next.

Luckily, I found these capacities are learnable. On my better days I treated the city like a classroom: a short daily reflection on one interaction that went well (what did I do? what did they do?), one that didn’t (what signal did I miss?), and one behavior to try tomorrow. Micro-journaling cultivates metacognitive awareness—the habit of noticing how you’re noticing—which underwrites both cultural intelligence and EI. Deliberate practice seems to help too: ask a trusted colleague to tell you, plainly, when you over-talk, under-react, or sound too sharp; mimic local salutations; rehearse a “soft open” to tough feedback. Small, repeatable routines compounded for me.

My reflection ends where it began, with that folded map from an undergraduate classroom. The Big Five still matter; they told me something true about my starting point. But the path I walked abroad depended more on how quickly I could learn the terrain: how well I listened, how carefully I calibrated emotion, how willing I was to try again when I misunderstood. The research has language for this—cultural empathy, flexibility, cultural intelligence, emotional intelligence—but what it felt like, day to day, was simpler. It felt like learning to be at home in someone else’s house.

References

- Han, Y., Sears, G. J., Darr, W. A., & Wang, Y. (2022). Facilitating cross-cultural adaptation: A meta-analytic review of dispositional predictors of expatriate adjustment. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 53(9), 1054–1096. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221221109559

- Gunkel, M., Schlägel, C., & Engle, R. L. (2014). Culture’s influence on emotional intelligence: An empirical study of nine countries. Journal of International Management, 20(2), 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2013.10.002