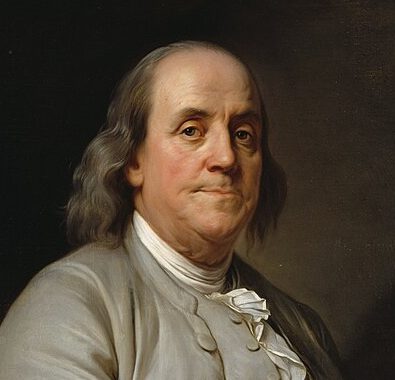

Few figures from our American past offer as compelling a template of an expatriate as Benjamin Franklin, whose own journey from colonial subject to international statesman mirrors the broader arc of American identity itself.

Franklin’s story resonates particularly deeply for those of us navigating foreign lands with American passports. He was, perhaps more than any other founder, a citizen of the world who never forgot his American roots—a man who could charm Parisian salons while securing the very survival of his fledgling nation. His legacy offers both inspiration and instruction for understanding what it means to represent America on the global stage.

Youth and Origins

Benjamin Franklin was born on Sunday, January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, which was then a British colony. His birthplace is at 17 Milk Street. Benjamin Franklin’s parents were Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger. Josiah Franklin was born in Northamptonshire, England, in 1657, and came to the Colonies in 1682. He worked as a candle and soap maker in Boston.

The circumstances of Franklin’s youth would have been familiar to many immigrant families throughout American history. Benjamin Franklin had 16 siblings. His father, Josiah, had seven children with his first wife, Anne Child, and 10 more with Abiah Folger. Ben was Josiah’s 15th child and his youngest son. In a household stretched thin by economic necessity, formal education was a luxury the family could scarcely afford.

Benjamin Franklin’s father wanted Ben to become a preacher, so he sent him to grammar school when he was eight years old. After less than a year, for financial reasons, Ben transferred to Mr. George Brownell’s school for writing and arithmetic. He stayed at the new school until he was ten, doing well in writing and badly in arithmetic. He then left school to work with his father in their candle shop.

The young Franklin’s struggles with formal education would prove formative in ways his father could never have imagined. Ben’s further education came from his own reading and lifelong conversation and debate with his friends. This early experience of self-directed learning would become a cornerstone of the American ideal of self-improvement—the notion that in America, your circumstances of birth need not determine your destiny.

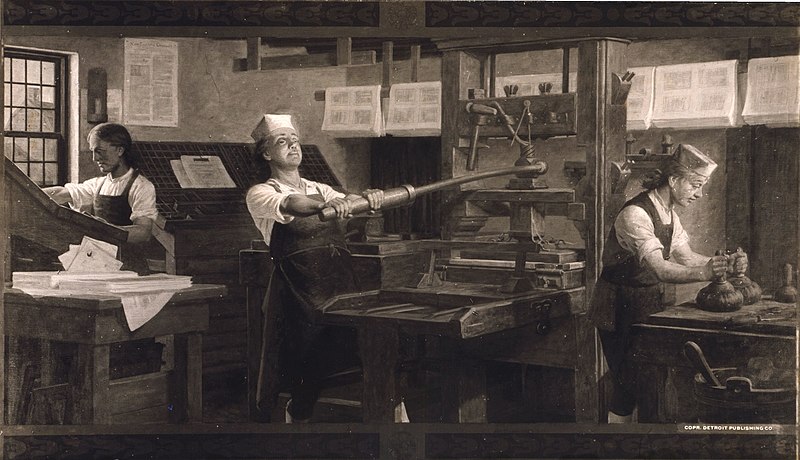

1718: Franklin starts as apprentice printer working for his brother James, marking the beginning of his professional life. Yet even in this apprenticeship, Franklin’s independent spirit shone through. He began by writing for his brother’s newspaper under the assumed name Silence Dogood. When he tired of reporting to his brother, he left Boston, visiting London in between his stays in Philadelphia.

Mounting Ambitions

Franklin’s decision to break his apprenticeship and leave for Philadelphia represented more than youthful rebellion—it was the first act of a man who would spend his life refusing to be constrained by convention. 1723: Franklin runs away to Philadelphia to become a journeyman printer, carrying little more than ambition and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

His first international experience came early. 1724: Franklin travels to London to continue training as a printer, an adventure that would prove crucial to his development. There, he started his own printing shop before gaining ownership of the Pennsylvania Gazette. This early exposure to London’s intellectual and commercial life planted seeds that would bloom throughout his career.

Upon returning to Philadelphia, Franklin demonstrated the entrepreneurial spirit that would define American commerce. 1728: Franklin opens his own print shop in Philadelphia, and 1730: Franklin enters common law marriage with Deborah Read. His domestic life provided stability for increasingly ambitious undertakings.

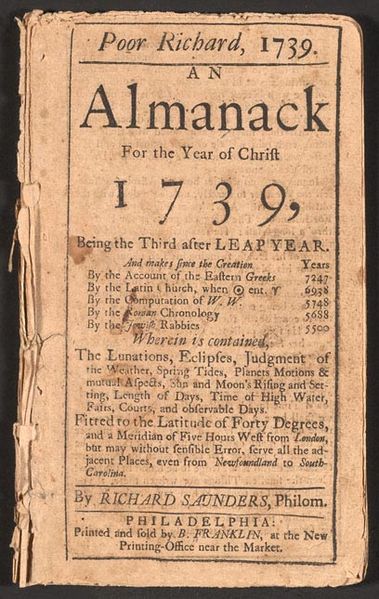

1732: Franklin launches Poor Richard’s Almanac, which became not just a commercial success but a vehicle for disseminating the practical wisdom and homespun philosophy that would make him famous throughout the colonies. Through pithy sayings and useful information, Franklin was already serving as an educator of his fellow Americans—a role he would never abandon.

The 1730s and 1740s saw Franklin’s transformation from successful businessman to community leader. As Franklin grew older, he developed into a community leader. He played an instrumental role in the establishment of notable Philadelphia institutions, including a library and the school that would later become the University of Pennsylvania.

The Jack of All Trades

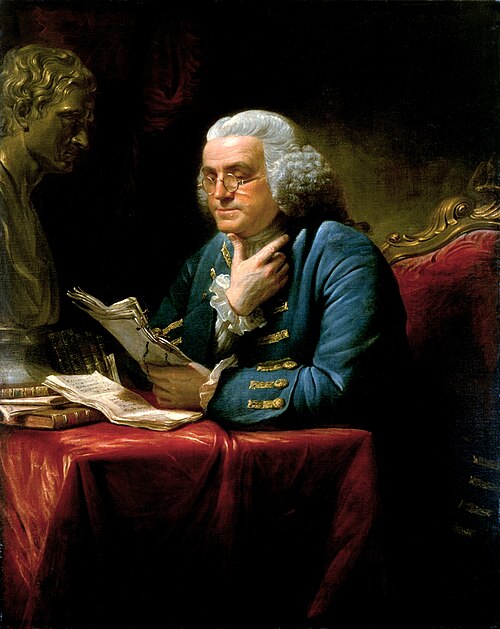

Upon retirement, Franklin added yet another title to his list of accomplishments: scientist. This transition marks one of the most remarkable chapters in Franklin’s life—his emergence as a figure of international scientific reputation.

Through his famous kite-flying experiment, Franklin verified that lightning transmits a powerful electrical charge. To protect against lightning’s ability to set homes ablaze, Franklin invented the lightning rod, which was designed to extend above buildings and to redirect lightning’s energy into the ground. 1752: Franklin invents the lightning rod and performs kite and key experiment represents a pivotal moment not just in Franklin’s career, but in the history of scientific inquiry in America.

The scope of Franklin’s inventiveness was extraordinary. Benjamin Franklin’s long list of inventions includes bifocals, the lightning rod, the glass armonica, a library chair, swim fins, a long-reach device, the Franklin stove, and the catheter. Each invention reflected his practical approach to improving daily life—what we might recognize today as quintessentially American pragmatism.

His scientific work brought international recognition. Among these were the Royal Society of London, which in 1753 awarded him its prestigious Copley Medal for his work in electricity, and the American Philosophical Society, of which he was a founder. Yale honored Franklin with the honorary degree of Master in Arts in 1753 for his scientific accomplishments.

Franklin’s intellectual curiosity extended far beyond formal science. 1761: Franklin develops his glass armonica, demonstrating his artistic sensibilities, while 1768: Franklin experiments with canal depths and devises a new alphabet shows his continued innovation in diverse fields.

The Father of American Diplomacy

If Franklin’s scientific achievements brought him fame, his diplomatic service secured American independence. 1775: Departs 36 Craven Street. Elected to Second Continental Congress. Proposes Articles of Confederation marked his entry into the highest levels of colonial politics.

Although Benjamin Franklin is best known as a Founding Father, he held this role later in his life. Franklin served on the Committee of Five that was tasked with drafting the Declaration of Independence. 1776: Signs Declaration of Independence and Sails to France as American Commissioner represents perhaps the most crucial transition of his career.

Franklin’s mission to France was fraught with danger and uncertainty. When he crossed the ocean that November he did so for the seventh time in his life—and for the first time as a traitor. Months earlier he had signed the Declaration of Independence; had he been captured at sea he would have been hanged in London.

Yet Franklin understood that American independence hinged on securing foreign support. Congress had declared independence in large part so as to attract a foreign partner in the American rebellion. For a long time that assembly discussed which should come first, the requests for foreign assistance or the formal break with Great Britain.

Franklin’s approach to French society was masterful. Despite his imperfect French—Franklin took home a hard-earned A- in oral comprehension, a B- in spoken French, and a downright F for his written skills—he became a sensation in Parisian society. His strategy was simple yet effective: Essentially he ignored them. He forged ahead, in fractured French, indifferent to the informers, oblivious—in a sort of Mr. Magoo way—to the social gaffes.

The diplomatic breakthrough came with news of American military success. That Thursday morning an American messenger galloped into Franklin’s courtyard… “Sir, is Philadelphia taken?” “Yes, sir,” replied the young officer, at which Franklin turned in defeat, his hands clasped behind his back. “But, sir, I have greater news than that,” the messenger called to Franklin’s back, “General Burgoyne and his whole army are prisoners of war!”

In 1778 Frankling negotiates and signs an Alliance with France which secured the support that would prove decisive in American victory. America could not have won the Revolutionary War without France. Schiff estimates the total value of French material and manpower at roughly $20 billion in today’s money.

Franklin’s diplomatic success rested on his ability to charm while remaining firmly American. Benjamin Franklin was the reason why France opened its coffers so wide to the unproven Americans. To put it simply, the French liked him and trusted him. Unlike his colleague John Adams, who approached diplomacy with demands, Franklin understood the power of making requests rather than ultimatums.

A Role Model for the Modern American International

Franklin’s legacy offers profound lessons for Americans navigating an increasingly interconnected world. His life demonstrates that effective representation of American values abroad requires not cultural imperialism, but rather cultural fluency—the ability to adapt to foreign customs while maintaining core principles.

Franklin was a man of protean imagination and of multiple disguises, but in France the role he played was that of himself. This authenticity, combined with genuine respect for his hosts, made him extraordinarily effective. His friends admired his most French of abilities: “At whatever moment you called,” remembered a young neighbor who did so regularly, “he always made himself available.”

Franklin’s approach to international relations was revolutionary for its time and remains relevant today. Franklin had the confident man’s ease about affecting subservience; he made it his business to acknowledge publicly the gratitude he genuinely felt. He understood that America’s strength lay not in arrogance but in its ability to forge genuine partnerships.

His commitment to learning never wavered, even in his final years. 1787: Elected President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery-Also signs the constitution shows Franklin’s continued evolution on moral issues. 1789: Writes last public letter urging the abolition of slavery demonstrates his willingness to reconsider and change his positions based on experience and reflection.

Perhaps most importantly for modern Americans abroad, Franklin embodied the idea that representing one’s country is both an honor and a responsibility. “Franklin was inventing the foreign service out of whole cloth. And he was, as we know from so many other realms, a brilliant inventor.”

For Americans living abroad today, Franklin’s example offers both inspiration and practical wisdom. He showed that effective cultural diplomacy requires genuine curiosity about other peoples and customs, combined with an unshakeable commitment to core American values of liberty, pragmatism, and self-improvement. His life reminds us that being American on the world stage means being both confident in our principles and humble enough to learn from others—qualities that remain as essential today as they were in the drawing rooms of Versailles.

In Franklin, we find not just a founder of our nation, but a template for global citizenship: intellectually curious, practically minded, diplomatically skilled, and perpetually committed to the idea that individuals and nations alike can reinvent themselves for the better. For Americans abroad, there could be no finer guide to representing the best of what our country aspires to be.

References

- Yale University. “About Benjamin Franklin.” Benjamin Franklin Papers, Yale University. https://benjaminfranklin.yale.edu/about-us/about-benjamin-franklin

- Franklin Institute. “Benjamin Franklin FAQ.” The Franklin Institute. https://fi.edu/en/science-and-education/benjamin-franklin/faq

- Benjamin Franklin House. “Franklin Timeline.” Benjamin Franklin House London. https://benjaminfranklinhouse.org/the-house-benjamin-franklin/franklin-timeline/

- Benjamin Franklin House. “Franklin & the House.” Benjamin Franklin House London. https://benjaminfranklinhouse.org/the-house-benjamin-franklin/

- History.com. “Ben Franklin in Paris: How He Won France’s Support for the Revolutionary War.” History Channel. https://www.history.com/articles/benjamin-franklin-france

- Schiff, Stacy. “Franklin in Paris.” The American Scholar. https://theamericanscholar.org/franklin-in-paris/