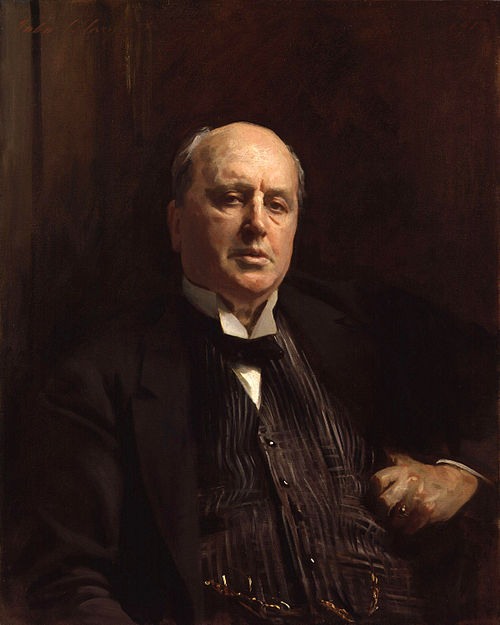

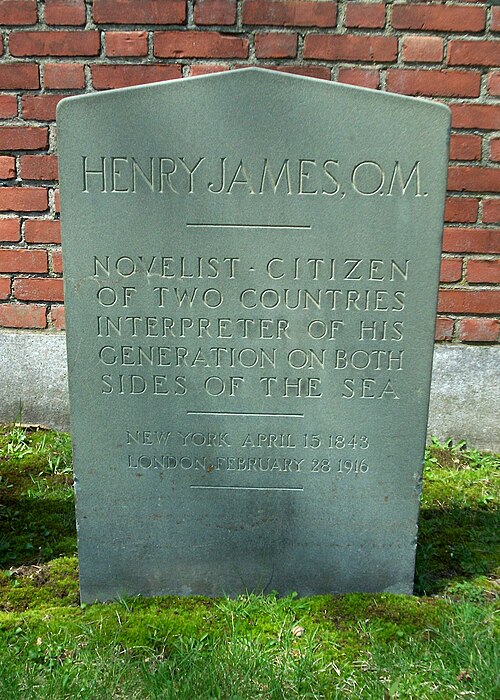

Henry James’s four-decade residence in Europe created the most sophisticated literary exploration of American expatriation ever written, transforming his personal cultural displacement into an innovative artistic method that would define the “international theme” in American literature. His expatriate status from 1875 to 1916 enabled him to examine both American innocence and European experience with unprecedented psychological depth,[^1] establishing him as the foundational figure in American expatriate literature and a crucial bridge between 19th-century realism and modernist consciousness.

James’s unique position as a permanent cultural exile—what the French call “dépaysement,” a queasiness of soul in a strange place—became both the source and foundation of his art. Unlike later Lost Generation writers who fled America after World War I seeking artistic authenticity, James expatriated deliberately in 1875 to gain the cultural perspective necessary for his literary project of comparing American and European civilization.[^2] His personal experience of living between two worlds for over forty years provided him with unparalleled insight into the psychology of cultural displacement, identity formation, and the complex negotiations required when American energy encounters European etrudition.

The making of a cultural interpreter

James’s expatriate journey began with a calculated artistic decision in 1875 when, after “a winter of unremitting hackwork in New York City,” he determined he “could write better and live more cheaply abroad.”[^3] Initially settling in Paris among Turgenev, Flaubert, and the French literary establishment, James realized within a year that he would remain “an eternal outsider” in France due to language barriers and impenetrable social structures. His 1876 move to London represented not just a change of address but a deliberate positioning as a cultural interpreter between the English-speaking world and continental Europe.[^4]

From his Bolton Street rooms off Piccadilly, James became what he called “a great social lion,” dining out 140 times during 1878-1879 and establishing himself in exclusive clubs including the Reform, Savile, and prestigious Athenaeum.^5 This social integration provided him with insider access to British aristocratic culture while maintaining his American analytical perspective. As he wrote to his brother William, “I am still completely an outsider here, and my only chance for becoming a little of an insider (in that limited sense in which an American can ever do so) is to remain here for the present.”[^6]

This perpetual outsider status became James’s greatest artistic asset. His European residence gave him what he called “the effect of detachment,” enabling him to observe both American and European society with analytical distance.[^7] His 1898 purchase of Lamb House in Rye, East Sussex, symbolized his permanent commitment to cultural exile,[^8] creating a literary salon where Conrad, Wells, Crane, and other writers gathered to discuss the emerging international consciousness that James had pioneered.

The international theme as literary innovation

James’s expatriate experience enabled him to create what scholars recognize as his most significant contribution to American literature: the systematic exploration of cultural contrasts between America and Europe that he developed into the “international theme.” This wasn’t simply cultural comparison but profound psychological analysis of what happens to consciousness when exposed to foreign civilizations.[^9]

In “Daisy Miller” (1878), James established the template for examining American innocence encountering European social conventions.[^10] Winterbourne, “an expatriate American who has lived in Europe for many years and has adopted European social conventions,” serves as the lens through which cultural conflicts are viewed.[^11] The novella’s tragic ending stems from cultural misunderstanding, as Daisy’s unchaperoned behavior challenges European codes while representing American individualism. When Mrs. Costello declares, “They are very common; they are the sort of Americans that one does one’s duty by not—not accepting,”[^12] James captures the expatriate community’s harsh judgment of newer American arrivals.

“The Americans” (1877) reversed this dynamic, presenting Christopher Newman as a self-made millionaire whose “guileless and forthright character contrasts with that of the arrogant and cunning family of French aristocrats.”[^13] James used Newman’s failed attempt to marry into French nobility to explore how American wealth and directness meet European aristocratic calculation. The novel demonstrates James’s growing understanding that cultural conflicts involve power dynamics beyond simple questions of sophistication.[^14]

Psychological depth in expatriate consciousness

“The Portrait of a Lady” (1881) represents James’s most profound exploration of expatriate transformation. Isabel Archer brings to Europe her “narrow provincialism and pretensions but also her sense of her own sovereignty, her ‘free spirit.’”[^15] Through Isabel’s encounters with European sophistication, James examined the transformation from American “innocence” to European “experience” as a complex psychological process involving both gain and loss.^16

The novel’s most psychologically sophisticated aspect lies in how James portrayed Gilbert Osmond as the corrupted American expatriate who has become “more European than the Europeans.” Osmond embodies what happens when Americans lose their essential character while gaining European polish—a cautionary tale about the dangers of complete cultural assimilation. “European corruption (expressed in an American expatriate, as is often the case in James’s fiction) is opposed to American innocence and emotional integrity,”[^17] creating moral complexity that transcends simple cultural preference.

“The Ambassadors” (1903), written after James’s 1904-1905 return to America, reflects his mature understanding of the expatriate condition. Strether’s transformation from Mrs. Newsome’s moral ambassador to an independent consciousness appreciating European culture parallels James’s own evolution.[^18] Strether’s famous declaration—”Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to”—represents James’s ultimate defense of expatriate experience as essential to full human development.[^19]

Direct testimony from the expatriate consciousness

James’s letters and personal writings provide extraordinary insight into the psychological reality of living between cultures. Writing from Europe, he maintained that “I have always my eyes on my native land,”[^20] yet his 1904 return to America after twenty years abroad produced profound alienation. In “The American Scene,” his account of this journey, James described himself as “a restored absentee” whose European-trained eyes found America increasingly foreign.[^21]

His letters reveal the emotional cost of cultural displacement. To brother William, he wrote with characteristic complexity about his position: “Always your hopelessly celibate even though sexagenarian Henry.”[^22] His intense correspondence with fellow expatriates like sculptor Hendrik Christian Andersen demonstrates the deep connections formed between Americans living abroad: “I hold you, dearest boy, in my innermost love, & count on your feeling me—in every throb of your soul.”^23

The psychological tension of expatriate life appears throughout his fiction in passages that capture the essential expatriate experience. In “The Portrait of a Lady,” the exchange about home resonates with profound displacement: “Ah, but where does home begin, Miss Stackpole?” Ralph enquired. “I don’t know where it begins, but I know where it ends. It ended a long time before I got here.”[^24] This dialogue articulates the fundamental homelessness that defines expatriate consciousness—the recognition that departure from one’s birthplace creates a permanent psychological displacement that cannot be resolved by simple return.

James’s artistic credo reflected his expatriate methodology: “To catch the colour, the relief, the expression, the surface, the substance of the human spectacle.”[^25] His European residence provided him with the detached perspective necessary for this cultural observation, enabling him to analyze both American energy and European refinement with equal insight.

Scholarly recognition of James’s expatriate achievement

Contemporary critics have established James’s foundational importance in American expatriate literature. Leon Edel’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography positioned James’s expatriation as essential to his artistic development rather than cultural betrayal.[^26] Modern scholarship recognizes that James’s “literary absenteeism” was, as William Dean Howells argued, “an expression and a proof of the modern sense which enlarges one’s country to the bounds of civilization.”[^27]

Academic analysis reveals how James’s treatment of expatriate themes evolved with historical changes. Early works like “Daisy Miller” portrayed Americans as innocent victims of European sophistication, but later novels showed “Europeans or Europeanized Americans who are the victims of the Americans” as the United States emerged as a world power.[^28] This evolution parallels “alterations in the international position of the United States itself,”^29 demonstrating how James’s expatriate perspective enabled him to anticipate America’s growing global influence.

Scholars emphasize that James’s approach differed fundamentally from both predecessors and successors. Unlike earlier American writers who lived abroad but remained essentially American in perspective, and unlike the Lost Generation who fled post-war America seeking artistic authenticity, James made the cultural encounter itself his primary subject matter, developing expatriation into a systematic method for examining consciousness and identity.[^30]

The unique perspective among American expatriate writers

“To write well and worthily of American things one need even more than elsewhere to be a master.“

Comparative analysis reveals James’s distinctive position in American expatriate literature. Where Edith Wharton used European settings as “straightforward channels for moral concerns,” focusing on corruption and artifice, James developed a much more complex psychological exploration of cultural displacement that influenced modernist literary techniques.^31 His pioneering use of limited third-person narration and stream-of-consciousness precursors enabled readers to experience “the narrator’s process of thinking, the slow dawning of consciousness, accompanied by a loss of innocence.”^32

The Lost Generation writers—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Stein—approached expatriation differently. Their war-driven exile produced literature focused on disillusionment and escape from American materialism, often maintaining distinctly American identities abroad. James’s pre-war expatriation served different purposes: cultural inquiry rather than escape, individual psychological focus rather than generational identity, and permanent cultural integration rather than temporary artistic sojourn.[^33]

James’s theoretical sophistication distinguished him from all contemporaries. As the National Endowment for the Humanities observes, James considered being American “an excellent preparation for culture” because Americans could “deal more freely than Europeans with forms of civilization not their own.”[^34] This insight enabled him to develop expatriation into a systematic literary method rather than mere biographical circumstance.

Broader themes of the American expatriate experience

James’s works capture universal aspects of expatriate psychology that transcend his historical moment. His exploration of cultural alienation appears in Isabel Archer’s observation: “There’s no such thing as an isolated man or woman; we’re each of us made up of some cluster of appurtenances. What shall we call our ‘self’? Where does it begin? where does it end?”[^35] This questioning of identity boundaries reflects the fundamental expatriate experience of discovering that selfhood is culturally constructed.

The search for European sophistication drives many of James’s American characters, reflecting what he called the “native American passion—the passion for the picturesque.” Americans in his fiction are drawn to Europe’s “vast, vague and dazzling” culture, seeking aesthetic and intellectual satisfaction unavailable in their homeland.[^36] Yet James consistently showed that this search involves complex negotiations between admiration and criticism, gain and loss.

The tension between American innocence and European experience provides the moral framework for James’s expatriate fiction. His ideal characters, like Isabel Archer in her final incarnation, retain essential American honesty while gaining European experience. James demonstrated that successful cultural adaptation requires preserving core identity while expanding consciousness through foreign encounter.^37

Most significantly, James captured the psychological reality of belonging fully neither to American nor European society. His expatriate characters exist in liminal spaces, translated beings who have been transformed by cultural encounter but never fully integrated into either culture. This condition of permanent cultural translation became James’s metaphor for modern consciousness itself.^38

The enduring legacy

Henry James’s expatriate achievement established the template for exploring cultural displacement in literature, influencing writers from Conrad and Joyce to contemporary authors examining globalized identity. His demonstration that expatriation could serve rather than betray American literature created possibilities for future generations of internationally-minded writers.[^39] His psychological realism and narrative innovations provided technical tools that modernist authors would develop into stream-of-consciousness and other advanced techniques.

Perhaps most importantly, James’s expatriate perspective enabled him to anticipate America’s emerging role in an increasingly interconnected world. His examination of American-European cultural dynamics prefigured many aspects of 20th-century international relations, making his work not only aesthetically significant but historically prescient. Through four decades of cultural exile, James created literature that transcended simple cultural comparison to explore the fundamental conditions of modern consciousness,[^40] establishing expatriation as both a legitimate American experience and a crucial perspective for understanding the complexities of cultural identity in an interconnected world.

His ultimate achievement lay in transforming personal displacement into artistic method, proving that the experience of living between cultures could produce literature of universal significance. James’s expatriate consciousness became a lens for examining not just American and European civilization, but the psychological processes through which all individuals negotiate between inherited identity and chosen experience in an increasingly complex world.

References

[^1]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Henry James | Novelist, Short Story Writer, Critic.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henry-James-American-writer

[^2]: Brooks, Peter. “Visions of Waste.” The New York Review of Books, March 24, 2022. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2022/03/24/visions-of-waste-the-american-scene-henry-james/

[^3]: “Americans Abroad.” American Heritage 12, no. 6 (October 1961). https://www.americanheritage.com/americans-abroad

[^4]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Henry James | Novelist, Short Story Writer, Critic.”

[^6]: James, Henry. Letters of Henry James, ed. Percy Lubbock. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

[^7]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.” Humanities 32, no. 4 (July/August 2011). https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2011/julyaugust/feature/henry-james-and-the-american-idea

[^8]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Henry James | Novelist, Short Story Writer, Critic.”

[^9]: Wan Roselezam Wan Yahya. “A Study on the International Theme, as a Prominent Subject in the Works of Henry James.” International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences 28 (2013): 85-91. https://www.scipress.com/ILSHS.28.85

[^10]: Literopedia. “Daisy Miller Summary And Themes By Henry James.” Accessed September 2025. https://literopedia.com/daisy-miller-summary-and-themes-by-henry-james

[^11]: SparkNotes. “Daisy Miller: Henry James and Daisy Miller Background.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/daisy/context/

[^12]: James, Henry. “Daisy Miller.” 1878.

[^13]: EBSCO Research Starters. “The American by Henry James.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/literature-and-writing/american-henry-james

[^14]: Literariness. “Analysis of Henry James’s Novels.” December 24, 2018. https://literariness.org/2018/12/24/analysis-of-henry-jamess-novels/

[^15]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Henry James | Novelist, Short Story Writer, Critic.”

[^17]: CliffsNotes. “Meaning through Social Contrasts.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/d/daisy-miller/critical-essays/meaning-through-social-contrasts

[^18]: Literariness. “Analysis of Henry James’s The Ambassadors.” May 22, 2025. https://literariness.org/2025/05/22/henry-jamess-the-ambassadors/

[^19]: James, Henry. “The Ambassadors.” 1903.

[^20]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^21]: James, Henry. “The American Scene.” 1907.

[^22]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^24]: James, Henry. “The Portrait of a Lady.” 1881.

[^25]: Washington State University. “The Art of Fiction by Henry James.” Accessed September 2025. https://public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/artfiction.html

[^26]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Leon Edel | Biographer, Literary Critic.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leon-Edel

[^27]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^28]: Academia.edu. “Shifting Portraits of the American Expatriate between the New and the Old World in Henry James.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.academia.edu/1455756/

[^30]: Agnes Zsofia Kovacs. “The Cultural Aspect of Experience in Henry James’s The Ambassadors and The American Scene.” Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/9177184/

[^33]: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Lost Generation | Definition, Writers, Characteristics, Books, & Facts.” Accessed September 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lost-Generation

[^34]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^35]: James, Henry. “The Portrait of a Lady.”

[^36]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^39]: National Endowment for the Humanities. “Henry James and the American Idea.”

[^40]: Open Book Publishers. “Henry James’s Europe – Preface.” Accessed September 2025. https://books.openedition.org/obp/797?lang=en